The earthquakes that recently rumbled Haiti, Chile and China also dominated the media with Richter-scale force. For a few days, it’s nonstop coverage as survivors are dragged from the rubble and families share their grief with the world. But as action shifts from the disaster itself to the arduous work of making life normal again — providing food, medicine, shelter and hope for those who have lost so much — the TV crews leave.

Only a year ago, we were praying for people in the Abruzzo region of Italy, where an earthquake had killed almost 300 and left more than 50,000 homeless. Thousands of buildings in and around the city of L’Aquila fell, including Renaissance churches and medieval landmarks. But as the weeks passed, public attention drifted to floods, terrorism, war, hurricanes and earthquakes elsewhere.

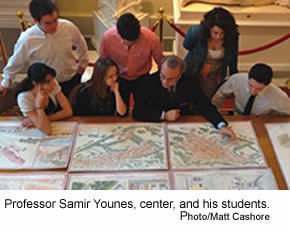

A group of students at Notre Dame’s School of Architecture will never forget the Abruzzo earthquake because they spent the past autumn semester drafting plans for rebuilding San Gregorio, a town of roughly 700 where 95 percent of the buildings were damaged, most of them beyond repair. At least a dozen townspeople died.

The class visited San Gregorio with Professor Samir Younés in August 2009, four-and-a-half months after the quake, and found residents living in tents pitched on the local soccer field. “It was a real shock,” say Brian Droste ’10. “You’d sit down to lunch with someone in the makeshift dining hall and realize that their house was over there in a pile.”

As the class toured the ruins of San Gregorio shooting pictures, making sketches and taking notes, fire marshals urged them to keep moving in case another building collapsed. “There were some places we could not go at all,” Droste says. “You could see laundry hanging on clothes lines. It had been there since the quake.”

Younés — who developed close ties with local officials across Italy as director of Notre Dame’s Rome program from 1999 to 2008 — traveled to L’Aquila in June 2009 to make arrangements for his students to study the damage and draft plans for reconstruction.

“Some towns were completely leveled and others nearby were not damaged at all. I wanted to show my students why that was,” he says, noting that the Notre Dame Architecture School emphasizes traditional architectural styles and building methods to ensure that structures last a long time. “That’s the heart of ecological, sustainable architecture — to build sound buildings and cities that endure.”

During seven days in Italy the class visited several communities. Younés zeroed in on San Gregorio for the semester-long design project. “The town was a disaster waiting to happen,” he says, noting that after a severe quake in 1703 workers from Rome were hired to reconstruct it. “In Rome they always used mud from the Tiber River for mortar between the stones, which works well because it’s rich in clay. But the mud in Abruzzo is different. As it dried, it turned to sand. Which worked fine to hold the buildings up, but not in an earthquake.”

The Notre Dame program trains architecture students to pay attention to local materials, styles and environments, Younés notes. The fate of San Gregorio shows why. Studying structures that fell as well as those that remained standing affirms the emphasis on traditional materials and methods. According to Younés, who has designed masterplans for cities in his native Lebanon as well as in Romania and Maryland, “it’s well documented that older buildings generally withstand earthquakes better. The problem with reinforced concrete, used in most buildings today, is that it moves all as one piece.” Masonry construction, such as brick or stone, moves as many pieces so it collapses less often.

“No one is saying we should build just like we did in the 15th century,” Younés adds. “That’s not rational. But it’s equally irrational to just throw out the best parts of what we have learned from centuries of architecture in favor of things that don’t last.”

Younés’ students were all familiar with Italy, having studied in Rome for a year as part of the Notre Dame curriculum. They were able to return thanks to funding from ND’s Nanovic Institute for European Studies, which promotes undergraduate research as part of its focus on contemporary European culture.

Anthony Monta, a Nanovic assistant director, says, “What attracted us to this project was the involvement of students in work that hits the sweet spot of Notre Dame’s mission — academic research that also has a social mission.

“I met with the students when they came back,” he adds, “and I felt their enthusiasm about engaging with a community and working on a real-world problem. This was not just architecture in the abstract.”

Returning to Bond Hall last August, the students — all in their fifth and final year — began work on plans for rebuilding San Gregorio. They spent the first half of the semester collectively drafting a master plan to rebuild the town, incorporating buildings they deemed salvageable along with new construction in the traditional local style. The rest of semester they worked individually on particular buildings.

“We analyzed the town as it was before, taking note of the porticoes, arcades, window styles and piazzas,” says Alejandra Gutzeit ’10. “But we also noticed that San Gregorio did not have a lot of public spaces. So we created a sequence of places to make it even more beautiful and lively than it was before.”

Students redesigned piazzas to make them more inviting and added a campanile tower to designs for the new church, paying attention to time-proven techniques for making it earthquake-proof. In recent years, San Gregorio had become little more than a bedroom community for nearby L’Aquila, so the class included a primary school and a broletto, an arcade combining a market and city hall, to restore the community spirit.

“We experienced a real sense of service in this project,” says Nicole Bernal-Cisneros ’10. “I felt I could give back to the world as a student of traditional architecture helping to rebuild an Italian hill town with integrity, even in a crisis like this. You need to build things that will endure.”

Younés planned to return to San Gregorio last month to present the students’ designs to people throughout the L’Aquila region. The drawings envisioning a new San Gregorio will be displayed publicly, and Younés hopes to find funding to publish a book. “I think we can help influence the discussion about how to rebuild,” he says, noting that student designs from an earlier Notre Dame class are now under construction in Brandevoort, Netherlands.

In Italy, reconstruction after earthquakes is usually done as quickly and cheaply as possible in a generic modern style that disappoints survivors who are proud of their historic communities. Younés believes the students can spark a breakthrough in thinking about reconstruction because they are less bound by professional conventions.

“People tend to associate Americans with the future,” he says, “so when we come into a community ready to study and learn from their traditions, that gets people’s attention and helps them value what they already have.”

--Story by Jay Walljasper

Jay Walljasper (jaywalljasper.com), editor of OnTheCommons.org and Senior Fellow at Project for Public Spaces, is the author of the forthcoming All That We Share: A Field Guide to the Commons Today.